Design systems are organized in an imperative, top-down, hierarchical way.

By this, I mean its maintainers decide on categories of content, and then how that content is ordered. This is done as a calculated bet to best serve the known and unknown audiences who consume the design system‘s content.

For example, GitHub’s Primer design system divides the world into a Getting Started guide, Primitives, UI Patterns, Components, React Hooks, and guidelines for Contributing. Shopify’s Polaris design system has has a similar approach with its navigation, but includes more options such as Content, Patterns, Tools, etc.

Everything in its right place

This is the tyranny of category made manifest. Organizing things in this way intrinsically means needing to put each item within the design system in a single location as either a parent or child-level object.

Due to sheer probability, this means that the organization approach may not fit every design system consumer’s mental model for how things should be organized. This means that discovering, referring to, and using the design system will be more difficult for some people than others.

This singular way of presenting content can impede design system adoption. It’s an understatement to say that this is counter to a design system’s overall goal.

Categorically different

Most design systems I’m aware of use organization via category, making it somewhat of a de-facto standard. However, there isn’t uniformity across all design systems for how many categories are used, or what each category is called. There’s also not always uniformity for how components are named.

Less external consistency means the design system adoption issue persists—consider a situation where a developer changes jobs and has to re-learn what components are called at their new place of employment. This is also to say nothing about names for component props, tokens, icons, etc.

Yes, the ability to use search a design system does help here some, but it is not always enough. It is also not the biggest concern, but I’m of the school of thought that this sort of friction adds up.

Other ways of organizing things

A folksonomy is a way of organizing things where the people who use the service are allowed to create and apply their own tags to things. Think of Gmail’s labelling capability, or adding hashtags on any number of social media platforms.

A folksonomy is used as an alternative to a more standard tagging system, in that the creating and stewarding of tags is in the hands of the people who consume the content, and not just the people who create the content.

There is no hierarchy other than what people create for themselves with a folksonomy. In this way they are more equitable in terms of power dynamics, in that they enable a bottom-up way of organizing things. This can serve one individual’s organizational needs, a group, or even an entire community.

This alternate approach makes folksonomies popular with social bookmarking services, as well as with fanfiction communities. An example of these two things harmoniously blending is the social bookmarking site Pinboard’s embracing of the fanfiction community.

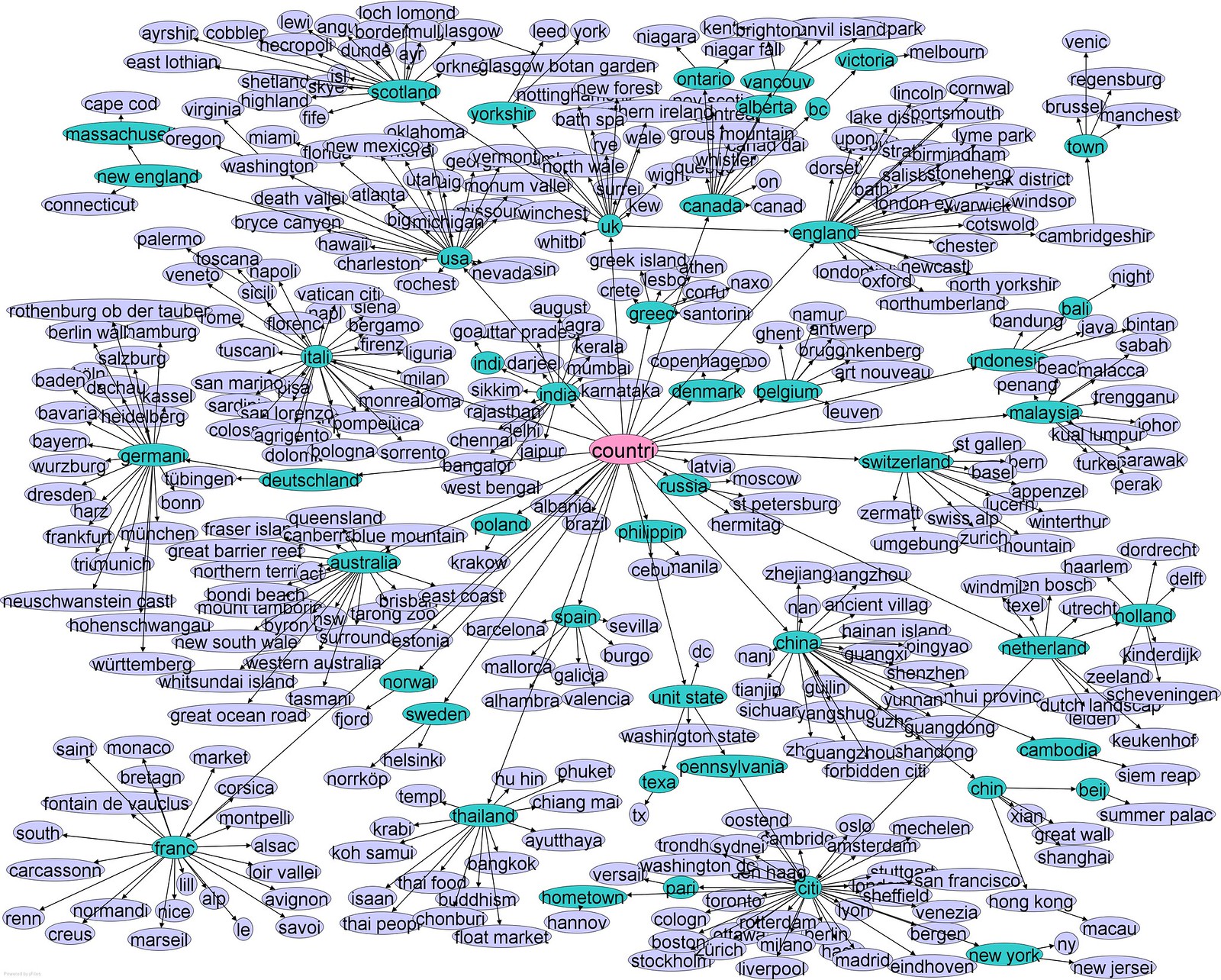

Mature folksonomies can contain an incredible amount of information. Check out this folksonomy for "country" organized via significance-testing, as shared by Kristina Lerman on Flickr:

What if?

I’ve long wondered what it would be like if we allowed design systems to support folksonomies.

Each person using a design system has a different way of thinking about it, as well as a different way of interacting with it. Anecdotally, I know a lot of people who rely on browser folders and bookmarks as a way to create a sense of order that works for their own needs.

I’d also like to set aside technical concerns for the time being. I do understand you’d need mechanisms for people to create identities on the design system site, and as well as creating, editing and storing the tags.

What would design system folksonomies look like?

People are creative, so there’s all sorts of things that could happen. To rattle off a few examples, we could see grouping by:

- Favorites, to quickly come back to,

- Something missing or outdated,

- Age,

- What a feature or larger initiative uses,

- Dependencies,

- Friction, to identify what isn’t working as intended,

- Supported tech stack,

- Use as a sub-component in other components,

- Common or shared props,

- Version,

- Status, such as stable, preview, or deprecated,

- Upcoming quarter, for planning purposes,

- Aliases,

- Things someone wants to try out,

- etc.

This is an incomplete list in that I can only guess what people would do. And that’s sort of the point!

Meeting people where they are creates surface area that promotes collaborative and emergent organizational structures that aid in discovery. This requires letting go of some control, which can be an uncomfortable thing for people who spend all day on design systems trying to enforce it.

Potential downsides

I’d be remiss if I didn’t be the villain for a moment. Any time you introduce open-ended input into a system you need to factor in how it could be used to abuse or exploit.

Sanitizing your inputs is a requisite for any public-facing service, so I won’t belabor that point. What I would like to call attention to is:

- The need to review what people are adding,

- A mechanism to report things added with the intent to cause harm, and

- A process to ensure something is done about it.

These considerations also require resourcing and effort to do. Unfortunately, this is a difficult thing to sell in our current working climate.

I am also not so naïve as to think you would not need reviewing and reporting capabilities for if a tagging system was made staff-only.

Curation

Reviewing also does not need to be thought about as an arduous chore. Fandoms treat the task as a way to help steward the community. Within the context of a design system, this could be a way to engage with the audiences that use it.

Curation also poses more potential opportunity. It could be a way to feature content from engaged contributors, which in turn creates positive associations with the design system and its maintainers. It could also be a way for the design system team to make informed choices about what is working and what needs attention.

What about auto-classifiers?

LLMs are actually pretty dang good at generating tons of tags for any corpus of content you throw at them.

When used as an auto-classifier, an LLM can be a great way to add a descriptive layer of metadata. Here, I’d like to highlight Max Woolf’s writing on how Buzzfeed uses it to create a hierarchal taxonomy for its gigantic library of content.

For a design system, it is also something that could be easily replaced with a decent searching service. The thing is, auto-generated information is bereft of meaning or intent.

An auto-classifier cannot answer the underlying why this information exists. It is is why I’m bullish on folksonomies, in that intent is integral to the act of human-powered tagging.

Design systems are not a solved problem

The way we create and organize design systems has largely settled into common patterns and practices. However, this does not mean the way to make design systems has calcified.

I’m not aware of any design systems that use folksonomies, but would love to be proven wrong!