There’s a secret mode that comes with almost all large ovens, refrigerators, dishwashers, and other large kitchen appliances. It is called Sabbath mode, and there is a very specific reason it is provided by the manufacturer.

No, it is not a mode made to placate Ozzy Osbourne. Sabbath mode allows someone to observe Shabbat, where Jewish law dictates that “work that creates” cannot be performed on the day of rest.

For example, an oven can be set to Sabbath mode to keep food prepared ahead of time hot. The work to create the food and the heat to keep it warm is done outside of the bounds of the holy day.

When activated, Sabbath mode overrides the oven’s safety features in order to avoid placing someone in the position where they need to expend effort in a way that work is created in a way that violates the day’s rules.

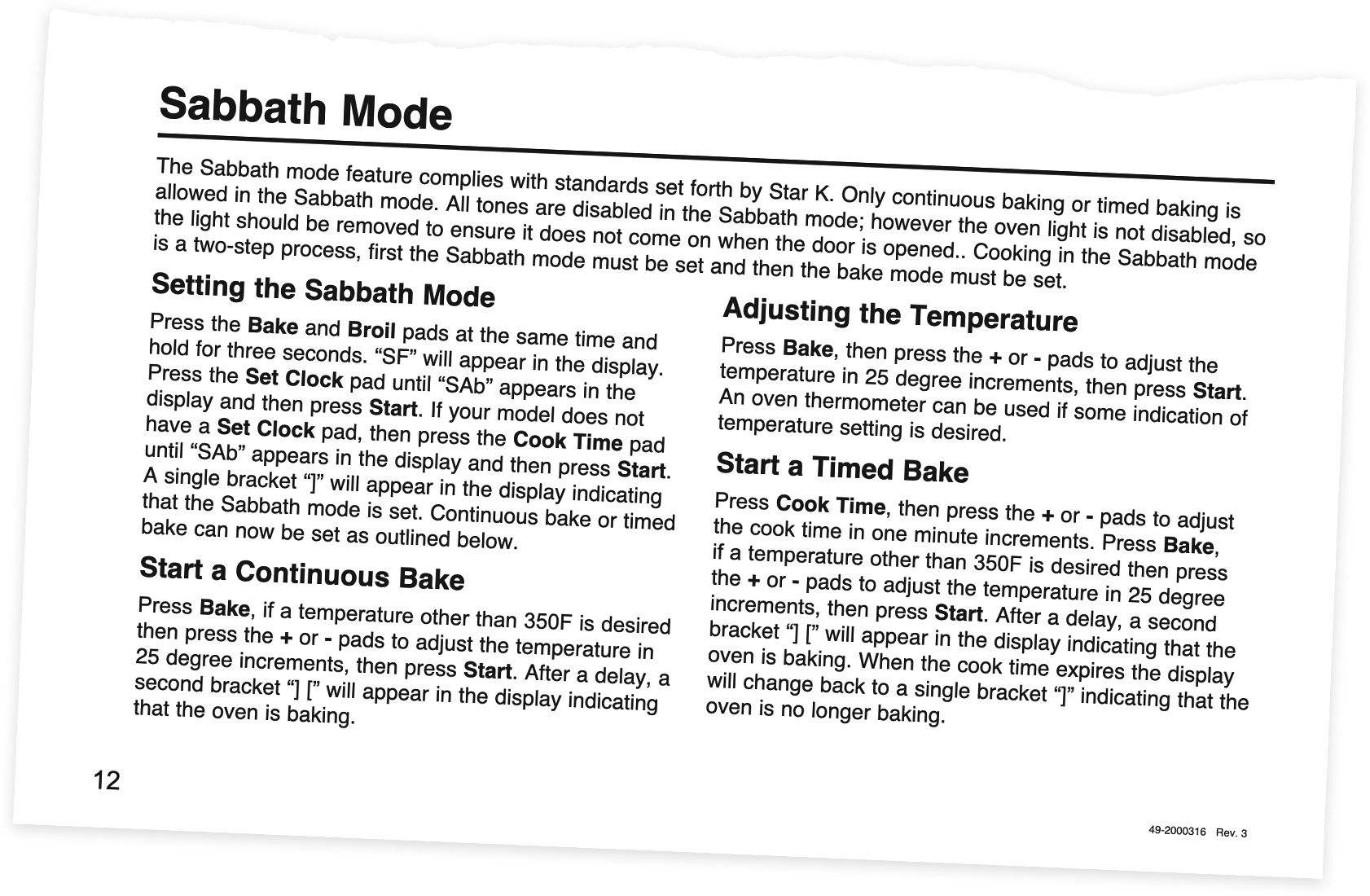

Activating a device’s Sabbath mode is usually not a straightforward affair. It usually requires a very specific, non-obvious, and convoluted set of button presses that must occur in a sequence specified in the dusty corners of an instruction manual.

Sabbath mode activation is almost always a highly intentional act made by an individual whose background means they know the feature exists and uses it for a very specific purpose.

This does not mean that unintentional activation of Sabbath mode can not also occur. Think the swiping of a cleaning rag over a touchscreen, a curious cat, or an unsupervised child.

Sabbath mode is an important feature for the people who rely on it. It is also not a very well-known feature.

The same parallel can be drawn for many assistive technology features. Every major operating system has multiple accessibility features built into them, but many of these features are obscure and only known by people who rely on them.

To continue this metaphor, you don’t have to be Jewish to enjoy the benefits of Sabbath mode functionality. You also don’t have to be disabled to enjoy assistive technology features.

That said, both Sabbath mode and assistive technology features are purpose-built to serve their respective audiences. We should not de-center these people when touting their virtues.

Like Sabbath mode, assistive technology features can also be accidentally activated through esoteric commands and keypresses. It may not always be obvious what was enabled, what it changes and when, or how to turn it off.

Additionally, not every Jewish person knows Sabbath mode exists. You have to read about it in a manual, be taught by someone who already knows about the feature, or be brought up in a household or community where the feature’s usage is commonplace.

Similarly, not every disabled person knows about, and consequently uses assistive technology features designed for their disability. My go-to example for this is prefers-reduced-motion, a toggle can save folks a lot of pain and discomfort that is also buried inside a few nested submenus.

Another thing to consider—and where this comparison starts to branch apart—is that most people know they are Jewish, or were raised Jewish. Not everyone who is disabled considers themselves so, or is aware of their condition(s) until they are triggered.

This means that assistive technology features and functionality may not be enabled, even though they could be beneficial to the person using the device where the features are present—for prefers-reduced-motion, learning about, and enabling this functionality oftentimes comes after the damage has been done.

So, what does this mean for you, a person who builds digital experiences?

First and foremost, just because an assistive technology feature exists does not mean it is guaranteed that a person who could benefit from its use knows the feature exists and is actively using it. This means designing and building an accessible experience as the default.

Second, the people who know about these features rely on them. This means that you should not remove, override, or otherwise subvert this functionality.

Third, you should be striving to include references in your documentation to relevant accessibility features and how they affect what you have made. Not only will this intentionality help to educate and spread awareness, but it will also help to normalize better practices across the industry.

Fourth, consider learning more about each of these features, why they do what they do, and how they came to be.

Fifth, don’t scoff at, downplay, or treat these features with derision. They are hard-fought, hard-won battles that represent survival and persistence in the face of indifference and oppression.

These five things touch on values that live at the core of Jewish faith. The values are ones that are important to me, even though I do not practice the religion:

- Avadim hayinu b’mitzrayim. Empathy for those who are victimized and in pain, and not oppressing strangers.

- Avoda. Work that contributes to the betterment of society.

- Kavana. Intention in how we think, how we communicate, and how we act.

- K’vod hab’riyot. Respecting and acting in a way consistent with the inherent dignity of humanity.

- Tzedek and tikun olam. Resisting oppression and improving an imperfect world full of pain, inequity, and hatred.

Finally, there is the concept of Shabbat itself. It emphasizes intentional rest as a method of creating contemplation and introspection.

Shabbat is a vital concept to honor in a world that increasingly churns out material without stopping to account for the diversity of human experience and the larger, wider impact.