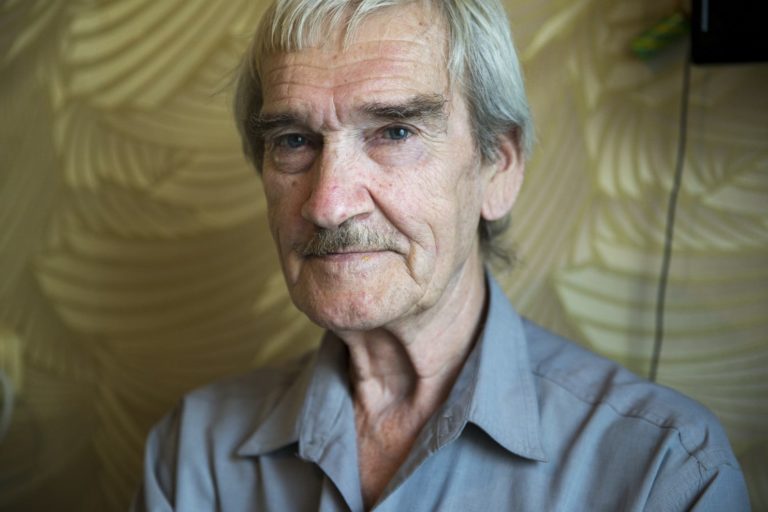

A lieutenant colonel in the Soviet Air Defense Forces prevented the end of human civilization on September 26th, 1983. His name was Stanislav Petrov.

Protocol dictated that the Soviet Union would retaliate against any nuclear strikes sent by the United States. This was a policy of mutually assured destruction, a doctrine that compels a horrifying logical conclusion.

The second and third stage effects of this type of exchange would be even more catastrophic. Allies for each side would likely be pulled into the conflict. The resulting nuclear winter was projected to lead to 2 billion deaths due to starvation. This is to say nothing about those who would have been unfortunate enough to have survived.

Petrov’s job was to monitor Oko, the computerized warning systems built to centralize Soviet satellite communications. Around midnight, he received a report that one of the satellites had detected the infrared signature of a single launch of a United States ICBM.

While Petrov was deciding what to do about this report, the system detected four more incoming missile launches. He had minutes to make a choice about what to do. It is impossible to imagine the amount of pressure placed on him at this moment.

Petrov lived in a world of deterministic systems. The technologies that powered these warning systems have outputs that are guaranteed, provided the proper inputs are provided. However, deterministic does not mean infallible.

The only reason you are alive and reading this is because Petrov understood that the systems he observed were capable of error. He was suspicious of what he was seeing reported, and chose not to escalate a retaliatory strike.

There were two factors guiding his decision:

- A surprise attack would most likely have used hundreds of missiles, and not just five.

- The allegedly foolproof Oko system was new and prone to errors.

An error in a deterministic system can still lead to expected outputs being generated. For the Oko system, infrared reflections of the sun shining off of the tops of clouds created a false positive that was interpreted as detection of a nuclear launch event.

The concept of erroneous truth is a deep thing to internalize, as computerized systems are presented as omniscient, indefective, and absolute.

Petrov’s rewards for this action were reprimands, reassignment, and denial of promotion. This was likely for embarrassing his superiors by the politically inconvenient shedding of light on issues with the Oko system. A coerced early retirement caused a nervous breakdown, likely him having to grapple with the weight of his decision.

It was only in the 1990s—after the fall of the Soviet Union—that his actions were discovered internationally and celebrated. Stanislav Petrov was given the recognition that he deserved, including being honored by the United Nations, awarded the Dresden Peace Prize, featured in a documentary, and being able to visit a Minuteman Missile silo in the United States.

On January 31st, 2025, OpenAI struck a deal with the United States government to use its AI product for nuclear weapon security.

It is unclear how this technology will be used, where, and to what extent. It is also unclear how OpenAI’s systems function, as they are black box technologies. What is known is that LLM-generated responses—the product OpenAI sells—are non-deterministic.

Non-deterministic systems don’t have guaranteed outputs from their inputs. In addition, LLM-based technology hallucinates—it invents content with no self-knowledge that it is a falsehood.

Non-deterministic systems that are computerized also have the perception as being authoritative, the same as their deterministic peers. It is not a question of how the output is generated, it is one of the output being perceived to come from a faultless machine.

These are terrifying things to know. Consider not only the systems this technology is being applied to, but also the thoughtless speed of their integration. Then consider how we’ve historically been conditioned and rewarded to interpret the output of these systems, and then how we perceive and treat skeptics.

We don’t live in a purely deterministic world of technology anymore.

Stanislav Petrov died on September 18th, 2017, before this change occurred. I would be incredibly curious to know his thoughts about our current reality, as well as the increasing abdication of human monitoring of automated systems in favor of notably biased, supposed “AI solutions.”

In unpacking Petrov’s skepticism in a time of mania and political instability, we acknowledge a quote from former U.S. Secretary of Defense William J. Perry’s memoir about the incident:

[Oko’s false positives] illustrates the immense danger of placing our fate in the hands of automated systems that are susceptible to failure and human beings who are fallible.

Further reading

- Stanislav Petrov: The Unsung Hero Who Saved the World from Nuclear Annihilation History Tools

- The reluctant hero: How a Soviet officer single-handedly prevented WWIII Gateway to Russia

- 41 years ago today, one man saved us from world-ending nuclear war Vox

- Stanislav Petrov: The Man Who Saved The World History on the Net

- A posthumous honor for the man who saved the world Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- Stanislav Petrov, 'The Man Who Saved The World,' Dies At 77 NPR

- My time with Stanislav Petrov: No cog in the machine Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- Trump Administration Providing Weapons Grade Plutonium to Sam Altman Futurism

- Pete Hegseth announces new military platform: 'The future of American warfare is here' MSN

- Cops Forced to Explain Why AI Generated Police Report Claimed Officer Transformed Into Frog Futurism